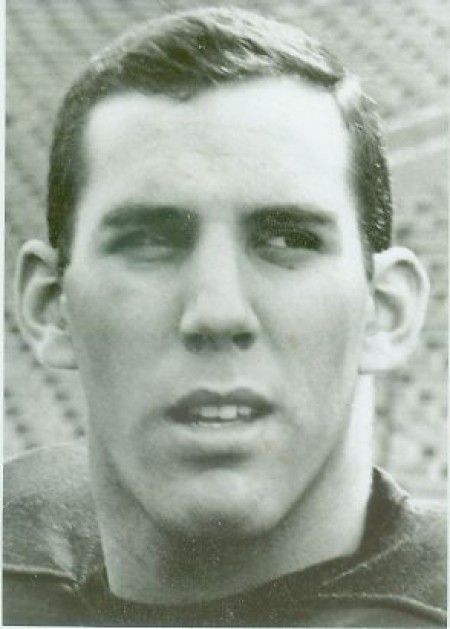

When it came Bruce Singman’s time to talk at the 1962 Illini senior football banquet, the departing fullback strayed from the usual jock-speak the crowd had come to expect.

Five decades later, he still hasn’t forgotten the looks on the faces of teammates, parents, professors and coaches at the downtown Champaign Hotel ballroom on that December day.

“The jaws dropped when I got up and stood at the lectern and did not say ‘I loved my time here in Champaign-Urbana playing for the Fighting Illini,’ but (rather) said that ‘My time here at the university was an enlightening lesson about life as I learned more from interacting with others from all walks of life than I did from the textbooks we had to read to pass our final exams each semester.’

“I could see many in the large group asking those around them ‘Who is that boy?’”

The answer: A George Huff Award-winning University City, Mo., product who’d go on to be a big-time Los Angeles sports and entertainment attorney and sports apparel manufacturer.

Singman has lived such a full, fascinating life, he could write a book. Actually, he did — he just hasn’t gotten around to publishing it yet.

If he ever does, this section — which he and former teammate and longtime friend Ken Zimmerman still chat about regularly — will surely be among the most talked-about:

“There were 119 of us on the freshmen team, including scholarship and non-scholarship walk-on athletes and 23 quarterbacks amongst the group. The standout quarterbacks from the very beginning included Mike Taliaferro and Jesse Jackson. Mike would become the Illini starting quarterback for our senior season, though he would suffer a season-ending injury during the course of our junior season after only three games.

“Mike was granted another year of eligibility to come back in 1963 and lead the team to the Big Ten championship and a victory over the University of Washington, 17-7, in the Rose Bowl on New Year’s Day in 1964. That was in the middle of my first year of law school at the University of California.

“Jesse, on the other hand, would leave the university after our freshman year because he was convinced that he could never become our starting quarterback because he was black — early signs that Jesse’s arrogance and misperception of his greatness would interfere with his ability to make sound judgments and do anything in his life that wasn’t for the purpose of drawing attention to himself.

“Jesse’s locker was next to mine. During spring practice of our freshman year — when the coaches were trying him at halfback and end because, with five or six quarterbacks ahead of him, they wanted to try to figure out a way to use his athletic ability during our sophomore year when we could play for the varsity — Jesse confided in me that he was going to leave at the end of the semester and return to North Carolina to attend school at North Carolina A&T State University in Greensboro because the (UI) coaches wouldn’t play a black quarterback.

"I subtly pointed out to Jesse that our starting quarterback for most of the past season was Mel Meyers, who was black.

“Mike and Jesse shared the quarterbacking position for the most part during the four scrimmage-like freshmen games we played against other Big Ten university freshmen teams, and I competed at the fullback position with Al Wheatland from Streator and Mike Summers from Evanston. Neither one of them was much of a defensive player so I had the edge amongst my classmates when lining up at the roving linebacker position.

“Football practices at the university under freshmen football coach Mel Brewer were a lot more difficult than the practices in high school under Stub Muhl, though, at the time, we compared Stub’s practices with the Bataan Death March. I was holding my own and fared pretty well amongst the all-state honorees recruited by the Illini coaching staff. I was smarter than most, if not all, of my teammates and my intelligence gave me an edge.

“I could follow my blocks and hit the holes and make the blocks I had to make from the fullback position on offense and could actually read the keys and react to make the plays from the linebacker position on defense. We attended the varsity games in Memorial Stadium and sat together as a group in the section on the east side of the stadium beneath the Block I reserved for the freshmen football players.

"The Block I was the section of students with huge colored cards they would use at halftime to spell out cheers, according to a sheet of instructions assigned to each seat.

“I think this orchestrated cheering originated at the university and became a tradition to be upheld by the fervent student football fans. If the University City High School sports teams weren’t known as the Indians when Stub was hired to coach the football team in 1928, then he must have been responsible for providing the name as a result of his playing days at the University of Illinois as a Fighting Illini, named after the Native American Indian tribe whose members roamed the Illinois plains during the years before the white man inhabited America and forced the Native Americans onto reservations.

“The first time I laid eyes on Chief Illiniwek — a university student dressed in full Native American costume who performed a spectacular ceremonial dance at halftime on the Memorial Stadium field — I was mesmerized. I remember my later regret of not being able to watch Chief Illiniwek perform during halftime of the football games when I was on the varsity squad and adjourned with my teammates to the locker room but I was still fortunate enough to watch Chief Illiniwek perform during halftimes of the basketball games.

“I felt a tremendous sense of loss when the nincompoops who ran the NCAA banned the university’s use of Chief Illiniwek as a symbol of the University of Illinois’ athletic department in response to illogical complaints of Native American sympathizers who bewilderingly thought that the use of Chief Illiniwek as a mascot for the athletic teams was in denigration — instead of celebration — of the Native Americans who inhabited America before the white man did.”

-Hiltzik.jpeg)

© 2026 The News-Gazette, All Rights Reserved | 201 Devonshire, Champaign, IL | 217-351-5252 | www.news-gazette.com